ENDURANCE OF THE SPIRIT

Wheeling, West Virginia

“They arrived in Wheeling at night,” Ed Gorczyca says of his parents. It’s the story he’s always known. When his mother awoke in the morning and saw the city's surroundings for the first time she said in Polish, ‘góra tam i góra tutaj,’ which means a mountain there and a mountain here.

“Because where she came from, they didn’t have hills like we've got here.”

The city of Wheeling is cradled in the upper Ohio Valley, a band carved by the Ohio River along West Virginia’s northern panhandle where the hills of the unglaciated section of the Allegheny Plateau, worn round and humble with age, tumble down to the water’s edge. Prior to European exploration, this was Delaware Indian hunting ground, and the name ‘Wheeling’ is derived from a native phrase meaning “place of the head” or "place of the skull" —a reference attributed to the legend of how a tribe decapitated an early white settler and placed his head on a pole at the juncture of Wheeling Creek and the Ohio.

The land wasn’t permanently occupied until 1769, when Colonel Ebenezer Zane threaded his way between those hills and down that same creek, laying claim to the land that would eventually become the city. The town was born into trouble as the conflicts between settlers and native tribes resumed. Vision, ingenuity, and grit ensured its survival and the transformation of the small river outpost into an important regional city.

By petitioning Congress, early Wheeling citizens helped bring the first federal highway—known as the National Road—from its origin in Cumberland, Maryland, across the Allegheny Mountains to Wheeling in 1818, thus connecting the Potomac and Ohio Rivers and facilitating the transit of goods and travelers between the cities of the East and the developing Western states. They followed this by constructing the Wheeling suspension bridge—the first bridge to cross the Ohio and the longest suspension bridge in the world at the time it opened to celebratory cannon fire in 1849. When the B & O railroad reached the city four years later, the transportation hub created by the confluence of river, road and rail was complete, establishing a base from which Wheeling would grow and thrive for nearly 100 years.

Ed Gorgzyca’s parents, Katherine and Anthony, were part of the wave of 28 million immigrants who arrived in America between 1880 and 1930 seeking greater freedom and new economic opportunities in the country’s burgeoning industrial centers. A friend of Katherine’s from back home in Poland had already made the move to Wheeling and implored Ed and Katherine to join her, promising a bounty of jobs. Indeed, the place Katherine Gorgzyca woke up to that morning was a city of more than 40,000, with laborers plumbing mines in the surrounding coal-filled hills and laboring in iron foundries, tool manufacturing plants, breweries, and glass factories. Although the city struggled with pollution and sometimes unsafe working conditions, the Wheeling of this period was molten; it was the aroma of cigars; it was free-flowing promise.

That Wheeling still haunts the minds of Ed Gorcyca and his contemporaries—a Wheeling that their grandparents and parents helped build into the wealthiest city per capita in America by the end of the 19th century and that remained vibrant through the days of their own youth before a decades-long decline took hold.

On a morning in October, the 78-year-old Gorcyzca stands in a dim room of the Polish American Patriot (PAP) club in South Wheeling. Three beer drinkers sit at the bar, one talks politics and the other two nod solemnly in agreement. Gorczyca explains that originally the PAP was a place where the large numbers of Polish families moving to South Wheeling in the late 1800s and early 1900s came to take citizenship classes and share each other’s company. Later, it got involved in sports leagues and today it continues to be a gathering place for the few Polish members of the community who are left.

Gorczyca says the neighborhood still buzzed when he was a child. Young people found work in the mines as his father had done, or when they got out of high school a family member would help find them a job at Wheeling Pittsburgh Steel or one of the other area factories and mills.

“This is South Wheeling from 48th to 43rd street,” Gorczyca says, pointing to a hand-drawn map and chart. “At one time, in these three blocks, we had 11 bars, eight grocery stores, two drug stores, three cleaners, four barber shops, one lumber yard, two gas stations, three slaughterhouses and one bakery.” His list continues, going on to include a theater, repair shops, and more. “There were 60-something businesses in this,” gesturing to the sketched neighborhood. “Now there’s not a heck of lot left.”

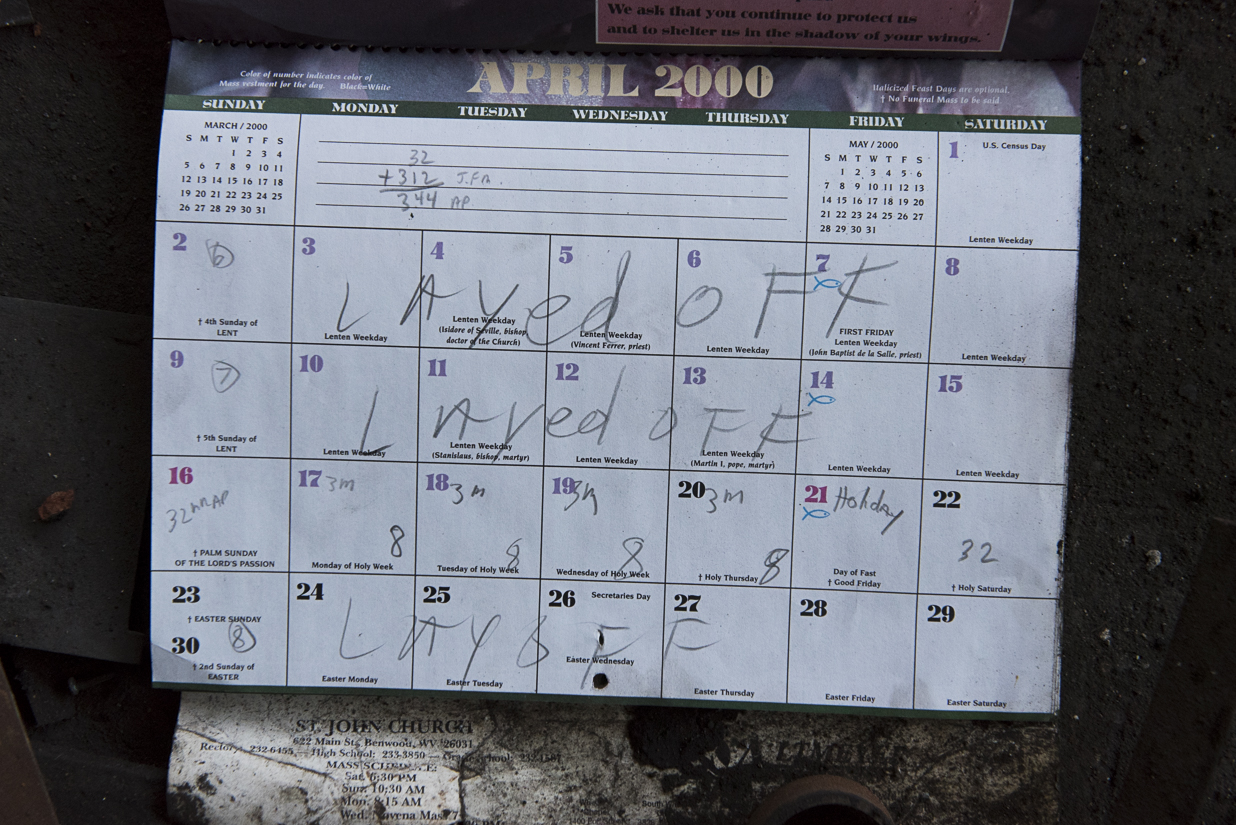

Gorczyca himself experienced the change in flashes. While still a young man in 1963, he accepted an offer from Wheeling’s Mail Pouch Tobacco that sent him to work as a salesman out of state. He spent nearly 40 years away, visiting once a year before he retired and moved back in 2000. Each time he returned, the city looked less and less like the one he remembered from his childhood.

Over the span of his lifetime, the collapse of the Upper Ohio Valley’s manufacturing base had helped fuel an exodus of young, working-age people. The city lost approximately one half of its population, declining from 61,659 people at the 1930 census to fewer than 28,000 today; demographers at West Virginia University’s Bureau of Business and Economic Research predict that the slide may continue into the foreseeable future. Viable employment opportunities remain in short supply, while out-of-town transient workers following the regional oil and natural gas boom have helped drive up rental prices in the city.

In spite of present hardships, some believe Wheeling has reached a potential turning point, with positive signs of renewal in the city for the first time in decades. Just as immigrants once navigated new territory to Wheeling, returning residents and a new generation of hopeful citizens are betting their talents, and their futures, on building upon Wheeling’s heritage and restoring the city physically, economically, and spiritually. It is a place determining an identity, with some resigned to eulogize what has been lost while others focus on what yet might be gained.

The La Belle Cut Nail Plant clung to life longer than most companies of its era. Today, its cavernous interior is a mausoleum to Wheeling’s 19th century industrial boom. Shafts of white, early afternoon light pour through high rows of windows, piercing the murk and falling in symmetrical patterns on a floor littered with nails. A shallow trench runs down a center aisle of the main room where banks of nail cutting machines were recently gutted. Nearby, a few pieces of grinding equipment acquired at a recent auction wait to be claimed.

La Belle was one of the city’s early industrial successes. Built in 1852, the plant produced four-sided cut nails, first with iron and then later with steel. This type, prized in construction work for its strength, preceded the round wire nails we more commonly use today. Until the late 1700s, nails had been made individually, with a blacksmith hammering four sides of the malleable end of an iron rod into a point. The nail-making machines that were put to use at La Belle and elsewhere in the mid 1800s revolutionized the process.

LaBelle grew to be the largest producer of cut nails in the world and was responsible for Wheeling once being known as “Nail City.” By 1874, the South Wheeling complex had expanded, housing 83 machines and employing at least 400 men.

A year-long strike at the facility in 1885 resulted in a shortage of cut nails and a subsequent influx of wire nails to make up the difference. Some workers were replaced by automatic nail feeding machines. La Belle would go on to be absorbed into the then failing Wheeling-Pittsburgh Steel Corporation before finally closing in 2010. It was one of two cut nail plants left in the United States at the time of its closing; only ten employees remained when the machines were shut off.

Four years after its closure, traces of a human touch still linger. A nail bent into a coat hook. A pair of work gloves tacked above a doorway with a message in black marker that reads “Joe’s Last Gloves.” Chalk tally marks on a wall.

The LaBelle building is slated to be demolished in early summer 2016. No one knows what will occupy the space once the building is razed, but developers have plans to build townhouse-style units on what is already vacant LaBelle property on the building’s south side to try to address the city’s affordable housing shortage.

Across town, in the neighborhood of Warwood, one of the remaining functioning remnants of the same era is trying to avoid a similar fate. Inside the Warwood Tool Company building, workers are making a piece for a track adze, and a waltz transpires near the slot furnace. William Davenport moves in a sequence of rhythmic steps, transporting a raw steel billet to the furnace’s hot, yawning mouth. He pauses momentarily, judging doneness by color, and then swoops in, clamps the glowing, white-hot billet and walks it to the next stage where it’s forged. The creation of a tool is a graceful dance, one that has been honed in one iteration or another at Warwood Tool for more than 160 years.

The founder, English immigrant Henry Warwood, had left the steel mills of Pittsburgh to open up a forging shop in Martins Ferry, Ohio, in 1854. There he made agriculture and mining tools in a stone oven and by hand on an anvil until he sold the business and it was moved to the Wheeling neighborhood named after him in the early 1900s. As the industrial revolution expanded in the Ohio Valley, so did the tool line, and they forged construction, steel cutting and railroad track maintenance tools. Adaptability is responsible for the company’s survival.

In the last few decades, the contraction of the American coal and steel industries and competition from cheaper, foreign-made products struck a blow to Warwood Tool and much of Wheeling’s industrial base. Warwood’s customers declined and the number of employees working the floor dwindled from over 100 down to 14.

This is the situation Logan Hartle and Phillip Carl, two 28-year-old friends who grew up in adjacent Marshall County inherited when they became co-owners in early 2015. Their vision for sustaining the company involves continuing to supply the still viable domestic industries while supplementing with sales to other countries that are currently overhauling their infrastructure. The core philosophy continues to be maintaining the Warwood tradition of using quality, American-made materials and local labor. It will be an ongoing process of trying to determine how to succeed where so many others have failed.

Tom Stobart, a playwright and owner of Paradox Book Store—the oldest used bookstore in West Virginia—is closing up for the day. Occasionally, the shop will break one hundred dollars. On an average day, like today, it’s closer to $15. Although the landlord has been kind with the rent, they barely make enough to afford it—the utilities and taxes pushed him to sell the house he lives in to keep the store’s doors open. Still, Tom and the bookstore he loves have managed to weather some of Wheeling’s most difficult years.

Stobart grew up in Wheeling and after a year of college, theatrical aspirations carried him to New York. Although he’s enjoyed some success over the years as a playwright, with two of his works produced in New York and Los Angeles and many others produced locally, his time in New York didn’t turn out as he had imagined. Struggling to stand out there, he moved back to Wheeling after a year and a half.

After a series of unsatisfying jobs, he remembered the Veterans Exchange bookstore he’d first visited as a kid, which had sold two things: paperback books for 15 cents and crafts made by disabled veterans. When he discovered that it had closed, Stobart bought it for $300. It was 1974 and he was 20 years old.

A few years after operating in the 11th street location—a building which has since been demolished—he moved to his current building, from which he has watched the town fluctuate around him. He remembers how the city had a chance to put in a mall downtown and how it went instead to nearby St. Clairsville—a fact some business owners throughout the city still point to as being responsible for nearly finishing Wheeling off after the loss of manufacturing jobs brought it to its knees. More recently, though, he’s watched parts of the city display buds of new life, though it has yet to reach his bookstore.

Stobart has been in poor health the past few years and though he has managed to defy grim prognoses, he’s been spending less and less time at the store around the books he considers sacred. He’s considered his options. “I’ve thought about giving it up and I just can’t,” he says. “Because I know that nobody is going to take it over and run it as a bookstore. Or if they do it won’t have anything like the spirit it has now.”

Stobart calls out to his assistant, Nikki, that he’ll be leaving for the day. He takes up his cane and glasses and begins edging his way around shelves that hold his 25,000-book inventory in aisles narrow enough that one can just barely walk between them without having to turn sideways.

Before he steps out onto the sidewalk, he pauses on the stoop, leaning his back up against the wall to rest. “I have no children. My folks are dead. I’m an only child. So there’s no family. I think Nikki might be interested in sticking around and doing this but that remains to be seen.”

He continues, “It just has to retain the flavor it has now, the philosophy it has now. I want people to read and I want people to read books on paper.” Despite a dire financial situation, behind him a hand-drawn sign encourages those who would like a book but can’t afford one to help themselves to a shelf by the doorway.

A glimpse of a city’s soul may be seen in its residents, business owners, and in its built environments, as well. The Capitol Theatre, one of the oldest and largest venues in West Virginia, originally opened on Thanksgiving Day in 1928 as a vaudeville house and theatre with an aesthetic influenced by the Beaux Arts style of the era. It seems that everyone of a certain age in Wheeling has a fond memory of the place to share, whether it was getting dressed up around Easter and taking pocket change to see a show, or spending their honeymoon there.

The Capitol has been home to the live country music show Jamboree USA, as well as the Wheeling Symphony Orchestra. Icons including Johnny Cash and Loretta Lynn have graced its stage. It closed for renovations for two years before re-opening in 2009.

“This is an honor. It’s a fabulous theater,” Harold Winley says before performing with his group at a rock ‘n’ roll and doo-wop show.

Winley explains that old-timers used to go in theatres and “feel the house” and that all venues have a distinct atmosphere. As for the Capitol, “It sounds good and it looks good,” he says. “This is a gem.”

Another one of Wheeling’s significant cultural institutions has been reincarnated. Lyceum Preparatory Academy was founded in 2008 as a response to the closure of the city’s prestigious Mount de Chantal Visitation Academy, a 160-year-old all girls school. The mansion in which the new school is housed is a testament to Wheeling’s past wealth. The Henry K. List House was constructed in 1858 and first served as the residence of the Wheeling-area merchant.

The Lyceum accommodates students in grades five through twelve and builds on Mount de Chantal’s legacy by offering an education curriculum that differs from most other offerings in Wheeling and elsewhere in its emphasis of the arts and by requiring Latin and violin. In addition to those subjects, which headmaster Judith Jones-Hayes believes will help improve standardized test scores, students learn teamwork by taking rowing and fencing. The classes are intended to be kept relatively small; there are only four students currently enrolled in Lyceum, with a few more expected to join in the near future.

And while the tuition is $5,000 per year, Jones-Hayes says students' parents have come from diverse employment backgrounds. She says that the cost alone should not be a deterrent for those who wish for their child to attend Lyceum, citing past success in securing donors to help finance an education at the school. “If they want to come here, someone will be found to make that happen,” she says.

Nevertheless, with its small class sizes, Lyceum is out of reach for most of Wheeling’s children, many of whom belong to families facing a host of challenges. In addition to joblessness, and housing prices, food insecurity is a major issue in Wheeling and has given rise to one of the city’s most visible organizations.

Grow Ohio Valley was started in 2014 by Danny Swan, a 28-year-old West Virginia native who had moved to Wheeling for college several years earlier and never left. After getting involved as a tutor with Laughlin Memorial Chapel’s after-school program, he became invested in the community. He had been struggling to find his own path in life at the time but discovered that the more of himself he gave, the clearer things became. After Wendell Berry’s work inspired him to start thinking about food inequality, Swan launched a couple of community gardens that eventually evolved into the organization.

It’s an organization that has become one of the faces of a subtle shift in Wheeling. “People are feeling much more positive about the Wheeling experience in general,” Swan says. “Wheeling is sort of turning into a happening place and I think we’re a part of that. We’re doing something that’s cool and exciting and changing the social structure of things.”

On a certain level, the goal of their work today is to bring a mobile market to those in the area who don’t have easy access to fresh produce and to teach people about urban agriculture, but it also simultaneously begins to address a deeper issue of connectivity in the city. “For me, it’s about relationships,” he says. “I think we have the opportunity to provide community for people who are lacking.”

Kate Marshall, who works at Grow Ohio Valley and whose daughter, Gabrielle, attends Lyceum Preparatory Academy, agrees with Swan’s sentiment and is also working toward strengthening bonds. Marshall was a single mother ready to move to an intentional living community in Philadelphia when she felt called to create something similar of her own back in Wheeling, which didn’t have anything like it at the time.

Now, Marshall’s home in East Wheeling is known as the House of Hagar Catholic Worker. She opens her doors to the city for meals on Sunday, offers her washer and shower to those who need them, and has taken in foster children who were in vulnerable situations—all of which are avenues for achieving her central goal for the city. “Our main mission is to be family to everybody here in this neighborhood,” she says. “The one thing I hope we are is hospitable love.”

Despite the challenges that exist in reimagining and creating a post-industrial city, signs of new life continue to arise. It was announced at the end of March that Reinvent Wheeling, an organization founded in 2009 to revitalize downtown Wheeling’s economy through micro-grants and entrepreneurial support, and Wheeling National Heritage Area Corporation, which works to conserve and promote the city’s historical attributes, have decided to merge to enhance their impact. While no singular effort alone will replace the manufacturing jobs that bled away from the city, the combination of these new positive currents could restore a sense of enthusiasm and draw people back to Wheeling once again.

What calls people to Wheeling today?

Is it the song of dusk enveloping the grand old bridge? Is it the warm, proud theater where Frankenstein used to appear glowing on celluloid at the midnight show? It could be something already lost to time, that elusive specter of the furniture store’s holiday display trains making their rounds, or another loved thing that left and might have returned to town.

Or it could be the sense of promise that was held in between these hills for someone’s parents, the promise that built this city and withstood a precipitous fall, a promise that says you could write the next chapter of Wheeling’s story.